I thought I would write up a short (ish) post explaining my reasons why I’m not a Christian. Individually these reasons might not be convincing, but their aggregate weight is vastly in favor of Christianity — especially modern Christianity – being false. I’m going to try to keep this post as short as possible since each reason could be its own post altogether.

Jesus Isn’t A Jewish Messiah

My witty catchphrase to sum this up: “If Christianity is true why are there still Jews?”. Some people who debate Christians regularly have probably noticed that apologists almost always take things out of context. Cherrypicking is the pejorative term. The funny thing is, Christians have to take the entire Jewish Bible out of context to “demonstrate” that Jesus was a Jewish messiah; Christians have been cherrypicking since the beginning. Cherrypicking Christians are as old as Christianity itself. The biggest irony, of course, is when a non-Christian quotes a particularly damning part of the NT or Jewish Bible and Christians deflect criticism by saying they’re taking that verse out of context. Pot. Kettle. Black.

Here’s a small sample “prophecies” about Jesus taken out of context:

- Isaiah 7.14 is not about Jesus. In context (i.e. all of chapter 7, at the least), the prophet Isaiah is trying to console king Ahaz. The historical situation was that the southern kingdom of Judah was about to be invaded by two foreign kingdoms. Ahaz wanted to make an alliance with a neighboring kingdom that wasn’t all that friendly with Judah and Isaiah is trying to convince Ahaz not to make said alliance and to wait for Yahweh’s deliverance. Verse 7.14 specifically is about using a contemporary pregnant, or soon to be pregnant, woman as a chronological marker to show when Yahweh will come to king Ahaz’s rescue. By the time that the child from the pregnant woman hits puberty, the two kingdoms (v. 16) that Ahaz is fretting over, the two kingdoms that are about to invade, will be defeated. Arguing over whether the verse says in Hebrew “almah” or “betulah” (or παρθενος in Greek) is irrelevant.

- Isaiah 53 is not about Jesus. In context (that is, all of the preceding chapters of Deutero-Isaiah [chpts 40 – 55]) the suffering servant is the personification of Israel, or Jacob. If you read from chapters 40 – 53 in one sitting, you’ll notice that this personification of Israel/Jacob has been going on the entire time. To take chapter 53 in isolation, something the author did not intend, and make it apply to Jesus, is to take the entire metaphor out of context.

- Isaiah 9.6 (or 9.5. depending on the translation) is not about Jesus. This verse says the messiah’s name will include EL GBWR (אֵל גִּבּוֹר). EL means “god” and GBR means “strength” or “might”. It doesn’t say the messiah will be a mighty god, but that his name will include Gabriel (GBR EL), which means “might of god” or “god is mighty”*. Just because it is a theophoric name doesn’t mean we should take it literally. Taking it literally is (surprise) taking it out of context. The order of the words in the name generally does not matter; Netanyahu (current Prime Minister of Israel) and Jonathan mean exactly the same thing (gift of Yahweh). Both names are composed of NTN — meaning “gift” — and YH (short for YHWH).

- Psalm 110.1 is not about Jesus. In context, Psalms can’t be a prediction about Jesus, or any messiah, since Psalms are not prophetic (effectively ruling out all of the Psalms that Jesus supposedly fulfilled). If the Psalms were prophetic, there should be other prophecies — that have nothing to do with Jesus — that the Psalms predict (there aren’t). But let’s say that the Psalms are prophetic just for the sake of argument. Psalm 110 says that it was written to David and not by David. Thus the “my lord” that this Psalm is talking about is David himself. It’s not David talking about “my lord”. In historical context, this Psalm was probably written by the Hasmoneans since they were the first ones to consolidate the roles of high priest and king into one office. The sectarian Dead Sea Scroll followers did not have this Psalm in their library, evidencing that it was written after their breakaway. And it makes sense that they would not have it, since the DSS group was antagonistic towards the Hasmoneans.

- There’s nothing in the laws of Moses that says that if someone follows all of the laws perfectly, then no one else has to. This assertion that Jesus “fulfilled” the laws of Moses is a wholly Christian invention. You can’t even say that Christians took this out of context since it is a soteriology that was invented whole cloth to validate Christianity. No one would think it were true unless they were already a Christian.

Of course, there are many more. But one thing is certain: Every single one of the so-called prophecies of Jesus are taken out of their original context to be made to apply to Jesus. Chances are, if someone purports that this or that Jewish Bible passage is a prediction about Jesus, and it’s only one or two verses, then it’s taken out of context.

Church History

Marcion (Μαρκίων) of Sinope (modern Turkey)

So here’s a simple lead question in to church history: “Why are there four gospels instead of one?” Most apologists will say that there are four gospels because each are separately giving witness to the historicity of the events they describe, much like four different people being interviewed after a traffic accident. Even though there might be minor contradictions, these minor contradictions don’t detract from the overall fact of a traffic accident. Unfortunately, this response completely ignores the historical situation that was actually happening in early Christianity and subtly assumes what it is trying to prove.

- Why are there four gospels instead of one? What was the historical situation that produced a fourfold gospel canon? Instead of using traffic accidents to describe religious history, we should use religion to explain religious history. Why is there, for example, one book of Joshua? Trick question; there isn’t just one book of Joshua, there are two. One, the Jewish version which is in the Christian Bible, and another one, the Samaritan version. So using religion as our explanatory example, we see why there are two books of Joshua: Religious sectarianism. Jews don’t consider Samaritans to be the true version of their religion and Samaritans don’t consider Jews to be the true version of their religion. If this explains why there is more than one book of Joshua, this probably also explains why there is more than one gospel. Religious sectarianism; Matthew wasn’t written to corroborate Mark, as the traffic accident explanation assumes, but was written to replace Mark. The same with every other gospel. There are more reasons why we know religious sectarianism is the answer:

- 1. The self-designation “catholic”. This comes from the Greek word καθολικός which means whole or universal. Small c catholic also means the same thing in English. Why would the “orthodoxy” give themselves that name? The same reason why the United States calls itself “united”. Making something “whole” or “united” that was, originally, well… not.

- 2. The Synoptic Problem. Mark was written first, which Matt and Luke rewrote to produce their gospels. People who independently report on a traffic accident don’t use the same exact words to describe the incident like Mark, Matt, and Luke do. If they did, then the police would rightfully be suspicious. To a lesser extent John also used Mark or a source that used Mark since John uses characters and towns we are pretty certain that Mark invented whole cloth (i.e. Barabbas; Bethany), this is yet again a point against independence, which is also an assumption of the traffic accident analogy.

- Expanding on the point about Jesus not being a Jewish messiah, many of these sectarian Christians did not cherrypick the Jewish Bible. Due to them reading the Jewish Bible literally, they realized that Jesus was not any sort of Jewish messiah. Moreover, they realized that the teachings of Jesus were incompatible with or contradicted the character and commands of Yahweh portrayed in the Jewish holy book (like many atheists do today) and concluded that these were two different gods. Some other sectarian Christians read the Jewish Bible a bit less literally than that and realized that Jesus could not be Yahweh in the flesh or born from a virgin. On the flip side, other Christians read the Jewish Bible more allegorically and more out of context than the Catholics did and said that Jesus was one god out of hundreds, or that Jesus was a god who was antagonistic towards Yahweh, who they reinterpreted as Yaldabaoth (possibly Aramic for “lord of chaos”), or that the serpent in the garden of Eden was a good being who was only giving humans knowledge, or other Christians who said it was the teachings of Jesus that saved and not his death (and chided those who “worshiped a dead man”) and so on and so forth.

- The first Christian who actually put together a canon for Christians was one of these sectarian Christians: Marcion. He is the one who realized that Jesus and Yahweh were contradictory and concluded that they were separate gods. Since they were separate gods, Christians needed their own canon since the Jewish Bible no longer applied; the Jewish messiah sent by Yahweh was yet to come. Marcion’s canon consisted of one gospel (remember, sectarianism) and 10 letters of Paul (which were probably all that existed when he did this). Marcion is also the first Christian to cite any written gospel (ironically Marcion means little Mark, just as Caesarion means little Caesar). The Catholics, in their catholicizing agenda, simply followed Marcion’s “gospel-apostle” canon format to capitalize and assimilate Marcionite Christians. This also meant bringing in Paul and making him more acceptable to Catholic dogma, which included editing his letters to undo the editing that Marcion probably did. Which means there is probably more than one voice in Paul’s letters that we read today.

- Apostolic Succession. It’s curious that, with all of this information in the background, Catholics have asserted that the concept of Apostolic Succession gives credence to their side of the story. However, in the timeline of Christian teachings, Marcion seems to have been the first Christian to actually claim his teachings go back to some sort of authentic apostle. We have no records of any Christians citing a teacher of theirs that goes back to the “original disciples” before Marcion (or his contemporaries Basilides and Papias). The redactional process of the gospels follows this same trend. The earliest gospels were unconcerned with who was authenticating the story. As we go along the timeline, moving diachronically through early Christian history, later gospels started to become more and more concerned with someone authenticating the narratives; starting with Luke’s introduction, to the gospel of Thomas’ introduction, to John’s concluding chapter saying that he got these stories from a beloved disciple, to finally gospels being written from first person points of view of the disciples like Peter or Judas.

All this means is that whatever or however Christianity originally started as, Catholicism (and all of its breakaway Christianities, like Protestantism) is necessarily a reaction to whatever Christianity or Christianities came before it. So even if original Christianity was true, Catholicism (i.e. all modern Christianities) is second to this original form and probably not true.

New Testament

“Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, see me after class. Your book reports are surprisingly similar.”

Following the conclusions of the previous section on Church History, what is the story behind the New Testament? Do we have the authentic teachings of Jesus, of Paul, of Peter or John? More succinctly: Is the NT reliable?

- First of all, all of the gospels were originally written anonymously. While later gospels (Luke and John) have allusions to eyewitness testimony, the gospels don’t actually get their attributions until the late 2nd century, when the Catholics were attempting to make their church the universal one by co-opting various heresies into their own traditions. We know that the original gospels were anonymous because no one who quotes a gospel prior to the late 2nd century Catholics ever quotes from Mark, Luke, John, or Matthew by name. First by quoting directly from it without attribution (“as the gospel says…”) or attributing them to generic apostles as appeals to original teachers gains currency. As I mentioned in the previous section, early Christian writings were all about revelation and very little about authentic teachers. As time progresses and sectarianism increases, the focus on authentic teachers increases and appeals to revelation decrease, eventually leading to attribution of the gospels (“according to Luke”, etc.).

- The first gospel written was Mark. All other gospels derive from this gospel either directly, like Matt, Luke, Marcion, etc., or indirectly like John. Because they all depend on Mark, the historicity of subsequent gospels strongly depends on the historicity of Mark. However, Mark seems to have written his gospel as a highly allegorical tale, inventing towns and people to serve literary purposes in his narrative (like the towns Bethany or Bethphage, the legion exorcism, feeding of the multitude with fish, the cursing of the fig tree as an allusion to the cleansing of the temple, which is an allusion to the destruction of the temple, the name Peter as a diss on Paul’s antagonist Cephas in Galatians, the names Barabbas, Jairus, etc.), and the first image of Jesus as a teacher appear in Mark’s gospel as well, which is also suspicious; Mark could have invented a wandering preacher Jesus for his own theological purposes. Other gospel writers copying from Mark in some fashion use these names, pericopae, and towns uncritically so they must not have done any “homework” or fact-checking either. And we can tell that they followed Mark’s basic outline because they all differ dramatically after Mark ends (at Mk 16.8). The part after 16.8 in Mark is itself an interpolation by someone unsatisfied with Mark’s original ending, summarizing the endings of the other gospels onto Mark.

- Marcion collected 10 of Paul’s letters. Why not all 13 (or 14)? Probably because the last three didn’t exist when Marcion did so. Marcion just so happens to have collected the seven of Paul’s letters that a large majority of NT scholars claim were written by Paul, and three that a smaller number think were written by Paul. He left out the three that a large majority of NT scholars conclude weren’t written by Paul. The seven authentic letters are Romans, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Galatians, 1 Thessalonians, Philippians and Philemon. The three contested are Ephesians, Colossians, and 2 Thessalonians. The three pseudepigraphal ones are 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus. But, we know that even the authentic and contested epistles have had more than Paul’s thoughts in them due to him being used in the battle between Catholics and Marcionites. There are interpolations. Romans 1.2-6 is probably an interpolation since it doesn’t fit the trend of introductions that Paul usually writes in his letters and the contents of this intro are anti-Marcionite. 1 Thess 2.14-16 is also likely an interpolation due to its anachronism. 1 Cor 14.34-35 is also probably an interpolation due to non-Pauline language. There are probably many more interpolations we cannot detect.

- Acts of the Apostles is first mentioned in the Christian timeline sometime around the end of the 2nd century. Which probably means that it was used as a weapon against heretics; especially heretics who relied solely on Paul: Marcionites. AoA reads as anti-Marcionite propaganda, which means it is less about the history of the early church and more about taming Paul and stealing him away from Marcion. Furthermore, the Christian genre “Acts of…” gained popularity in the 2nd century, so it wouldn’t make sense that this work was written in the 1st century and sat around for almost 100 years untapped in the battle against heretics. Lastly, the work seems to get some of its information from Josephus, who published his last works around the end of the 1st century. So the earliest possible date for it is the beginning of the 2nd century.

- The letter writer John, the gospel writer John, and the revelation writer John are all not the same John; at least, the letter and gospel writer are not the same as the apocalypse writer. Namely, the gospel writer and epistle writer never name themselves but the apocalypse writer does. Not only that, but the most important evidence is linguistic: The apocalypse writer seems to have been a native Aramaic speaker writing poorly in Greek**. Contrary to that, the gospel/epistle writer has a very good grasp on the Greek language, using puns that only make sense in Greek***. An argument could be made that the apocalypse writer was one of the original disciples of Jesus (assuming he had any, since “disciples” are only a title in Mark’s gospel), but the gospel and epistle writer had too good a handle on Greek to have been an Aramaic speaking disciple of Jesus.

- The same situation happens with the epistles 1 & 2 Peter, James, and Jude. These were written in Greek, much better Greek than the apocalypse of John, which counts as evidence against original authorship by disciples of Jesus. 1 & 2 Peter have the same problem as the letters and revelation of John. 1 Peter is written in a different style of Greek than 2 Peter.

With all of this in mind, it doesn’t seem as though the NT is reliable as far as reconstructing Christian history. But it is a reliable collection of works to elucidate what type of struggles were going on in the 2nd century.

The Jesus Needle in the Christ Haystack

If the NT is not reliable, especially reliable about Jesus, and the history of how the church formed is explained by highly volatile religious sectarianism (mostly about different interpretations of Jesus) then how do we know anything about the “historical” Jesus? Most reconstructions of Jesus by scholars are done by assuming that one of the issues I wrote about above do not apply, or simply hand wave them away. But with all of this information in the background, it seems as though if Jesus existed, the balloon of myth that surrounds him is simply too large to determine with any certainty what a historical Jesus would look like. So at this point, I’m agnostic about the guy’s existence.

A major escape clause for the historicity of Jesus is appealing to oral tradition. The assumption being that if there was oral tradition, then there must have been a wandering preaching Jesus to start it all. Unfortunately this simply does not follow. Tradition guards its secrets jealously; traditions are only kept because they had utility in storytelling (or in battling heretics), not because of how historical they were. The subjective value of a tradition within a community has no bearing on how historical the tradition is; a tradition could be invented whole cloth that was intended for great storytelling (like Mark’s entire gospel), but this has no bearing on how historical the tradition is. At the most we can tell how young or old a tradition is, which, again, is only an indicator of how long the tradition was useful in storytelling. It is not a necessary indicator of historicity. And as we notice from the trend of church history, early Christians were unconcerned with authenticity of things here “on the ground” and more interested in revelations. The focus on the primacy of the earthly teachings of Jesus or his immediate disciples is a later development of church history, and this development only evolved to combat the rampant sectarianism.

Christianity In The Wider Pagan Matrix

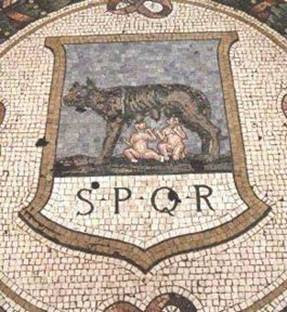

Romulus and Remus, born from the Vestal Virgin Rhea

Ok, so if it is highly likely that none of the now common dogmas about Jesus either came from Jesus himself or his immediate followers, where did they come from? This is actually pretty easy, and can be summed up in the question “How many Jewish kings were worshiped as a god?”

- How many Jewish kings or high priests were worshiped as a god? It turns out that this number is big fat zero. On the other hand, the number of non-Jewish kings and heroes worshiped as gods is much, much higher. It seems as though as soon as the Jesus cult was ported over to non-Jews, then many of the now common ideas about Jesus began to take hold. If Jesus was thought to be a king to pagans, then he must also be a god. For example, Augustus Caesar (where we get the month August from) had the official title “son of god”. He was the adopted son of Julius Caesar (where we get the month July). But these pagans who were interested in Christianity were faced with a conundrum. If Jesus is a god (since he’s a king) then which god is he? There is only one god in Judaism. The only solution was to combine them; Jesus became Yahweh in the flesh. The only problem was that this changed Jesus from a (supposedly) wandering Jewish preacher to a Greco-Roman god.

- The same deal with the virgin birth and resurrection. Many heroes or kings in antiquity were thought to be born from virgins. It only follows that the same mytheme would be applied to Jesus once pagans started converting to Christianity. Stories about man-gods and heroes coming back from the dead also abound in antiquity. Richard Carrier made a tongue-in-cheek comment that stories of demi-gods and heroes coming back from the dead in antiquity were as common as Law and Order spin-offs today. Christianity’s claims are just “Law and Order: Judaism” or “CSI: Jerusalem”. As I wrote about in a pretty recent post, the most famous city in Western society was supposedly founded by a guy who was born from a virgin, ascended to heaven, and resurrected from the dead: Romulus, who founded Rome over 2,500 years ago. Coincidentally, Romulus would have been born from a virgin around the same time that Isaiah wrote 7.14.

- For the more intellectual pagans, they revered the creative force of the Platonic god’s reason: the Logos. It was only logical for Christians (by way of Philo) to apply this Logos to Jesus. Intellectual Christians spun it so that if one was worshiping the Stoics’ Logos then one was in reality worshiping Jesus. The concept of martyrdom, also, originates from pagan society. At least, the culture of respecting martyrs. The very word itself, “martyr” in Greek (μαρτυρία), means witness or testimony. For the Greeks, the best witness to your claims is dying for them. Looking death in the face, and standing firm in the face of injustice, is a theme as old as the Homeric cycle. Christians also seem to have borrowed the Eucharist ceremony from contemporary Mithraists.

Very little of the dogmas of modern Christianity need to have been preached and believed by either Jesus or the early Jewish Jesus cults. Once Christians began preaching to non-Jews, the previous culture and memes that these pagans believed also became a part of the emerging Christian memeplex.

Christian Virtues Are Not Virtuous

1. Faith is not a virtue. Sure, there are quips about how Christians are “gullible” because of faith, but that’s not the angle I’m going for. It’s not the gullibility of faith that makes it not a virtue, but the self-deception of faith that makes it not a virtue; it’s the constant hammering that faith is a virtue which makes it non-virtuous, ironically enough.

If one is constantly prodded to believe something, not because it was true, but because believing in it in and of itself was its own virtue, then this pushes “truth”, no matter where it’s at, to second-class status in deference to this belief; this faith. This actually has nothing to do with gullibility. This has to do with Dennett’s “belief in belief” (also here). If some idea or value is promulgated as a better virtue than believing in whatever was “true”, then when the two are juxtaposed — when “truth” and faith come into conflict — if one doesn’t follow “truth” then one is engaging in some form of deception. Moreover, if one doesn’t actually believe some claim, but is constantly nudged to believe in something because one is told that it is virtuous to believe in it, then one is not being honest with oneself. This, also, is necessarily self-deception.

Of course, I think that this self-deception (i.e. “faith”, Christian faith) is the reason why Christians take the Jewish Bible out of context, and why church history panned out the way it did. Truth was not a concern for any of these Christians. Faith was. And in order to bolster faith, one would have to take a passage of Jewish scripture (like Isaiah 7.14) out of context and shoehorn it to apply to Jesus. In order to bolster faith, one would have to take a document of unknown authorship and provenance — like the gospels — and slap the name of an apostle on it. In order to bolster faith, one would have to take an epistle not written by you, but had some sort of authority, and subtly inject your own views into the pen of this authoritative voice.

Christian faith is not a virtue. Faith cannot be a virtue if one is concerned with the truth; if one is concerned with honesty. If we are concerned about truth, if we think that believing what’s true is a virtue, then we should only believe in high probability events (because reality isn’t black and white enough for binary “truth” and “lie”) to have a high probability of being “virtuous”. Because I value “truth”, I only value high probability beliefs and explanations. And because I value high probability beliefs, I do not value Christian faith.

2. Christian philosophy is arrogant. Basically, if the only two options for us being here are (1) accident or (2) intelligent design by god, then I’m not arrogant enough to pick the second option. Us being here “by accident” is the more humbling option, since it actually places us in our realistic relationship with the universe. If we were put here on purpose, especially by some god, then this purpose becomes “divine” and thus we become something closer to the center of the universe. Of course, pre-modern Christians actually believed that we were the center of the universe and fought tooth and nail against (scientific) ideas that proposed any alternatives. Which makes sense, when you consider that Christians, generally, place more worth on faith than on truth.

To think that the creator of the universe, assuming that one existed, created the universe for our benefit, wants a “personal relationship” with us, and eventually took on human form and died “for us” cannot honestly be anything other than abject narcissism.

3. The Christian worldview doesn’t answer any questions. Yeah, Christians like to say that the reason for xyz phenomenon is because “god wants it”, but this doesn’t actually answer the question, it just pushes the question back one peg. If the purpose for us being here is to give glory to god, or something else that has something to do with god, then what is god’s reasons for doing anything? If god has no reason for his existence, then every value and teleology that you attach to this god becomes meaningless by association. In other words, in the grand scheme of things, Christianity doesn’t give any more value to life than any other theistic worldview or even atheism.

Christian Belief Through The Lens Of Cognitive Science

Ok, so. If aliens came down to Earth today and we tried to explain Christianity to them, would they say “Interesting! Tell me more” or would they say “uhhh…”? In other words, why would we believe that a guy could come back from the dead in today’s modern world? Even more than that, why would we believe that his coming back from the dead has any repercussions for anyone living today? What’s the possible connection?

- Of course, no one (at least, no one that I know) became a Christian through objective inquiry into Christian history. They became Christians for the same reason they speak English; their overwhelming surrounding culture spoke the “cultural language” of Christianity and they learned that cultural language at the same age(s) they learned their native language. And just like we use our native language to explain things that happen to us, we use our cultural language to explain “religious experiences”. The English language is just as pervasive in the U.S. as Christianity. One would only notice this if you didn’t speak either language. An Arab who grew up in a predominantly Muslim country would do the same. They would use their native language (Arabic) and their cultural language (Islam) to explain any “religious experience” they would have as well. The truly miraculous thing would be to see a native language and cultural Hindu explain a religious experience using English/Christianity when they don’t know anything about either English or Christianity.

- All religions, not just Christianity, take advantage of our cognitive biases. The most entrenched one is the fear and avoidance of death. If we are given an option of either living forever or dying, our innate biological drive will compel us to pick the live forever option, no matter how illogical it is. As a matter of fact, it could be argued that every single cognitive bias that psychologists and neurologists have discovered helps inculcate religion from critical thought. Which might explain why psychologists are among the least religious professions. One of the most pervasive cognitive bias I see in debates (not just in regards to religion) is confirmation bias, where we engage in “motivated skepticism” of ideas that are contrary to what we already believe.

- Then there is the unreliable feeling of certainty. Certainty is an emotion, just like love or anger. If we can get angry about a situation that we imagine happening, a situation that hasn’t actually occurred, then we can feel certain about a situation that hasn’t actually occurred as well. Neurological processes explain why we get sudden epiphanies; when we think a thought, even though it might leave our conscious awareness, the thought can still be processed and worked on subconsciously in the background. This is why some people might think that some random thought is from a god or some spirit being, when in actuality it’s just from the part of your brain that “thinks” without you thinking it. On top of this, the feeling of certainty feels good, and the feeling of uncertainty does not. This alone should make the feeling of certainty highly suspect. Unfortunately, religious believers think that this feeling of certainty, this good feeling, is unearthly and attribute it to the “inner witness of the holy spirit” or other religious terms.

Why should we be wary of cognitive biases? Because most biases act on a subconscious level. And if they work on a subconscious level, then we are not aware that they are controlling us. Most people falsely believe that they are “critical thinkers” but almost none of these people has studied any cognitive biases. In order to be a good thinker, one has to know how the brain thinks. As tautological as that sounds, no one actually follows that advice. One cannot be a critical thinker without knowing common pitfalls of rational thought; common pitfalls that toss us into the chasms of irrational thought. And if these biases are working at a subconscious level, and we are being led around by them towards comforting, yet false, beliefs, then someone who does know about cognitive biases can lead us around by the nose into positions that we don’t necessarily want.

Τέλος

So these are my general reasons for not being a Christian. I didn’t really touch on the existence of a god because I don’t think that’s necessarily relevant to specific Christian claims.I might save that for another post, but I generally think that if a god exists, he does so naturally and/or is some sort of non-personal god. Hopefully, one can be anything but Christian (Jewish, Muslim, etc.) and will agree with everything I wrote above. But yeah. These are my reasons why I’m not a Christian, and will probably never be a Christian again.

————-

*The ‘i’ in many theophoric names is possessive, which would mean that Gabriel means “my god is mighty”. Gaborel (or EL GBWR) would be “god is mighty” but is still a theophoric name; Ezekiel 14.14 has the name Danel (god is judge) not Daniel (my god is judge)

**cf. Rev. 1.4 ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν καὶ ὁ ἐρχόμενος is bad Greek grammar; ὢν, which means “being”, should probably be εστιν to mean “is”. ὁ ὢν is a quote of the LXX version of Ex. 3.14 which only makes sense in that context as a rough translation of the original Hebrew pun

***cf. Jn 3.3ff the pun between “born again” and “born from above” only makes sense in Greek [note, this is a link to a joke that is lost on a non-native English speaker as an example] which is why the pun doesn’t make sense for modern readers and we have to stick to only one translation of άνωθεν. The “again” meaning of it.

Chriss Pagani

December 27, 2011 at 5:42 pm

This is a great post and I hope it ends up being widely-read. As a former Christian, I realize how difficult it can be to overcome ones own biases in order to make an accurate assessment of the information you've provided but I hope some of my religious friends will try, anyway.

J. Quinton

December 30, 2011 at 7:56 am

Thanks! I was hoping to write a shorter post since those are easier to read, but I wanted it to be a summary that did justice to why I don't believe. Still, I hope it gets widely read too 🙂

Vinny

January 2, 2012 at 1:03 pm

Great post.Faith is not a virtue.I often think of the Parable of the Talents. Two of the servants put what they are given to work and make it into something more which pleases the master. One of them buries what he is given in the ground and displeases the master.If there is a God, He gave me my mind and the ability to reason. Picking a religion and believing all its teachings on faith seems to me to be equivalent to burying God's gift in the ground. I don't see how that could be pleasing to any God who would be worthy of worship.Why are there four gospels instead of one?According to Irenaeous, there are four gospels because there are four winds and because cherubim have four faces. Apparently, that was the "state of the art" apologetic for the gospels in the late 2nd century, which leads me to suspect that they didn't have any real evidence for any of their traditions.

Hendy

January 3, 2012 at 4:19 am

Fantastic post. I hope to do something like this on my own blog soon. You laid out a fantastically organized and easy to read/follow statement of your case. Well done and I learned some neat tidbits, too! Now subscribing to your blog…